Using ROVs to visually monitor marine ecosystems has experienced a rapid increase over the past two decades as a result of cheaper, smaller ROVs becoming available as well as improved access to oil and gas sector ROVs (e.g. through the SERPENT initiative; Macreadie et al. 2018) and philanthropic ROVs (e.g. Schmidt Ocean Institute). Researchers have used ROVs in monitoring the impacts of invasive species (Whitfield et al. 2007), assessing marine protected areas (Dauble 2006, Torriente et al. 2019) assessing population trends in demersal fishes (reviewed in Sward et al. 2019), mapping of benthic habitats (García-Alegre et al. 2014, Torriente et al. 2019), examining diversity in reef communities (including on vertical walls; (Robert et al. 2017, Price et al. 2019), detecting marine litter (GESAMP 2019), and assessing spatial and temporal changes in fish and sessile benthos associated with artificial structures (such as oil and gas infrastructure; McLean et al. 2017, Bond et al. 2018).

While ROVs can be used for deploying a variety of sensors, as well as taking samples of substrata and organisms (Table 10.1) they are also used to generate spatially accurate photomosaics and finescale digital elevation models. Multibeam data which is often available with accurate georeferencing can provide important information regarding habitat types and structural complexity but is often limited to cell resolutions of 50 cm to 5 m. Finescale digital elevation models from ROV photomosaics can be done at 1-10 cm cell resolution, and on vertical structures (something AUVs currently struggle to achieve), thus enabling extremely detailed structural information to be extracted (Robert et al. 2017). Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, the benefits of using ROV to provide digital elevation models is that they also provide colour information (via the photomosaics), which is crucial for identification of species and evaluation of condition (e.g. live vs. dead coral).

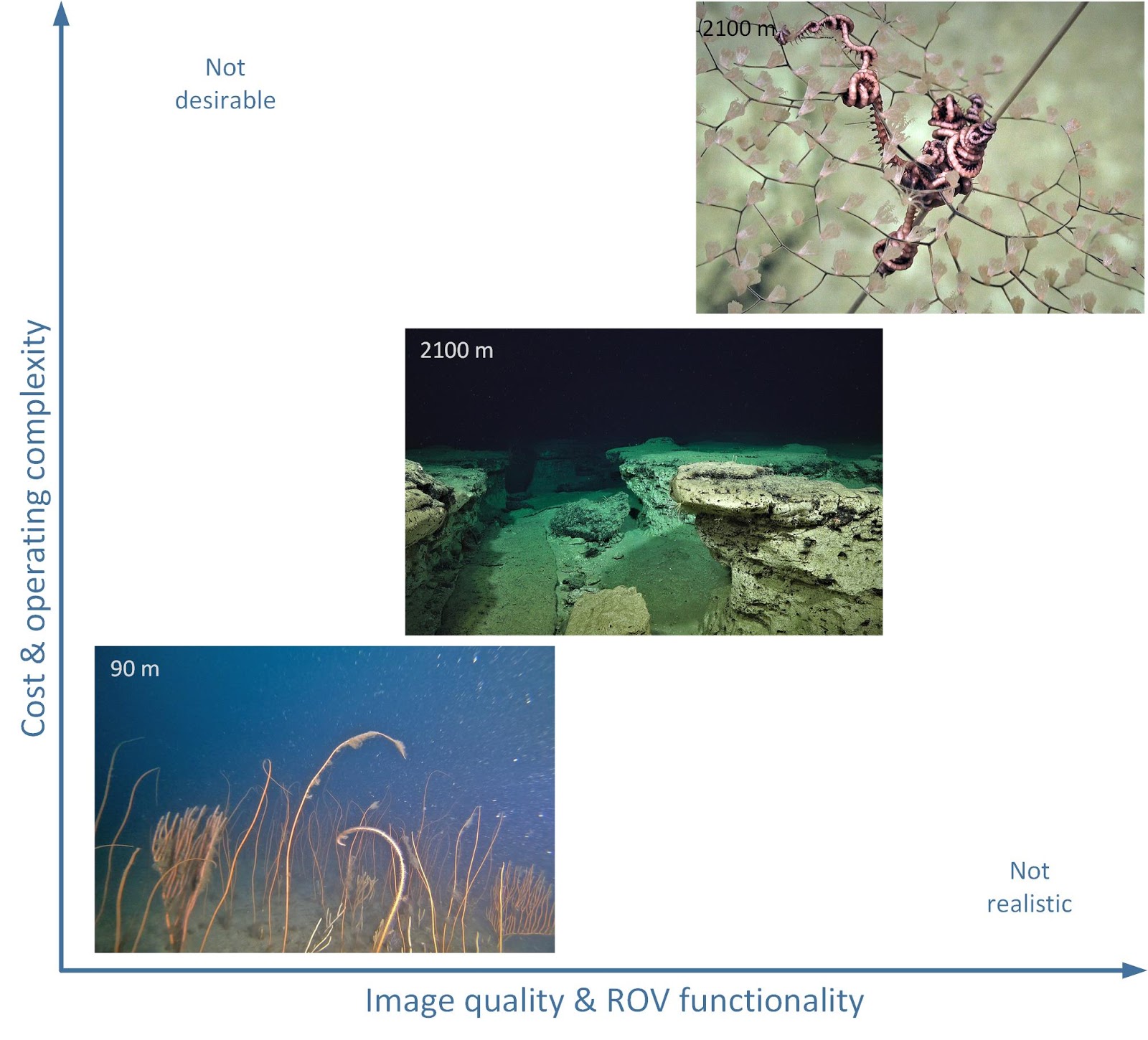

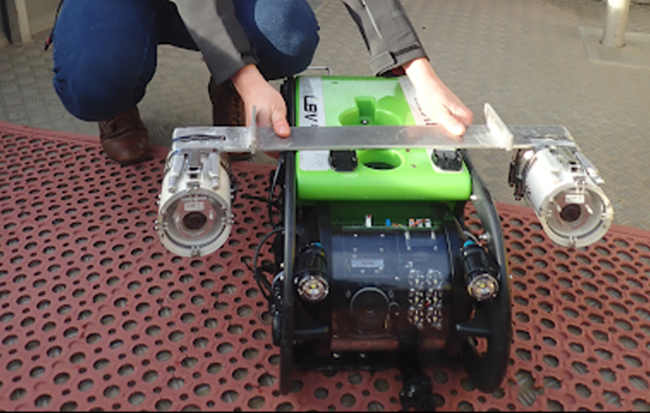

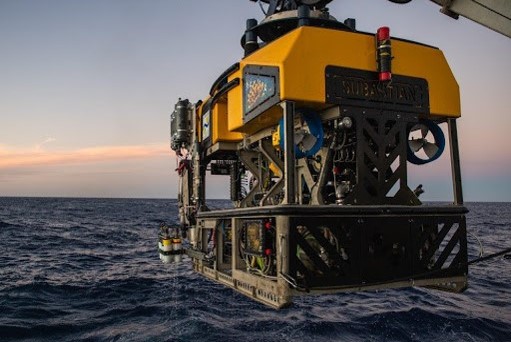

ROVs are not without their limitations when visually monitoring organisms. Different classes of ROVs are better suited to certain situations and components of a species assemblage (Table 10.2). There is generally a trade-off with high-quality macro-imagery and ROV functionality associated with high costs and technical requirements (Figure 10.1). When using ROVs for visually monitoring marine organisms, researchers should consider the potential effects of differing light intensity and wavelength, impacts of sound intensity and frequencies (for example, large hydraulic ROVs are noisy), and consequences of vehicle speed, size, altitude on survey bias particularly on mobile organisms. Research suggests that a combination of these factors can have substantial effects on the data collected (Stoner et al. 2008, Ryer et al. 2009, Rountree & Juanes 2010). While all sampling platforms have associated biases, the limited access to work-class ROVs and a steady uptake of cheaper smaller vehicles may make ROVs particularly prone to this bias. This is particularly important if different vehicles are used between regions (e.g. inside vs outside no-take reserves) or across time series sampling.

A key advantage that ROVs have in a monitoring context is their ability to be dynamically controlled in ‘real time’ across a range of depths and habitats. This is because data are streamed real time which means that the vehicle can survey vast areas with constant supervision and can be easily focused on areas of interest. ROVs are the only marine imagery systems available in Australia that are able to readily collect quality imagery from highly rugose environments, including vertical rock walls, steep slopes, and overhangs. These environments are prevalent in many marine parks, along the continental slope and offshore reefs. Similar to AUVs, when equipped with acoustic positioning (e.g., ultra-short baseline, USBL), ROVs can be piloted along precisely defined transects, at a constant altitude, with the geolocation of individual still images along this path as well as forward facing stereo-video (along with other sensors if required/fitted). The geolocation of imagery and flight paths allows relatively precise repeat transects to be conducted for monitoring purposes, and also for the imagery to be used to ground-truth multibeam sonar (Ierodiaconou et al. 2011), assessing the effectiveness of marine protected areas (Torriente et al. 2019), as well as for modelling the environmental factors driving species’ distributions (Salvati et al. 2010, García-Alegre et al. 2014, Lastras et al. 2016). Although ROVs have been shown to collect comparable reef fish assemblage data as diver-operated video and slow towed video (Shchramm et al 2019), they are uniquely suited to collect data in environments that are otherwise challenging to other sampling platforms.

Figure 10.1: Sample images showing the tradeoffs for different ROVs: [left]: sessile invertebrates from Hunter Marine Park from a BlueRobotics BlueROV (with a heavy kit upgrade) fitted with stereo GoPro HERO7 Black cameras, [middle] limestone outcrops along a canyon slope in the Gascoyne Marine Park from the ROV SuBastien’s situational camera, and [right] brittlestars entwined around a black coral from the ROV SuBastien’s 4K camera.

Table 10.2: Summary of ROV classes and considerations associated with each when used for monitoring Australia’s marine estate (table modified from JNCC, 2018).

| ROV class | Class I: Observation |

Class II: Observation (with payload option) |

Class III: Work |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Definition and capability | Typically < 40kg in weight these vehicles are primarily intended for observation only. Fitted with inbuilt camera and lights, may be able to handle one additional sensor (such as USBL), simple grabber claws, as well as an additional stereo-video camera. | Larger vehicles than Class I, weighing ~100-150kg, are capable of basic physical sampling and observations. Capable of carrying multiple cameras and sensors as well as simple gabber claws. | Weighing <~5000kg, these vehicles have a broad carrying capability and operational conditions (e.g. depth and currents). Usually used in deeper waters (i.e. off continental shelf) these are the most complex and versatile of ROVs used. They are often used in the Oil and Gas sector. |

| Examples | BlueROV, Boxfish, DeepTrekker, Fusion, Ocean Modules V4 S300, OpenROV, Seabotix LBV300, Trident, VideoRay Pro4 |

Ocean Modules V8 M500, Pollox, Phantom, Saab Seaeye Falcon (DR)/Cougar XT |

Argus Mariner XL/Worker, Hercules; Holland, Isis; Jason 2; Kiel6000; Ocean Modules V8 L3000, SuBastian |

| Scale of operation^ | Fine (<20m) - Meso (200m - 1km) | Meso - Macro (>1km) | Meso - Macro |

| Max. operational conditions | Depth: <100m Sea state: <2m Current: <1.5kt |

Depth: 0 - 300m#, Sea state: <3m Current: <3kt |

Depth: >300m, Sea state: <4m Current: <4kt |

| Deployment type | Manual | Manual (<300m depth) or vessel A Frame/crane and winch or Launch And Recovery System (LARS) package. | LARS package or vessel A-frame/crane (for shallow deployment). A moonpool is a further option. |

| Tether management | Free swimming - tether connected to ROV. Clump weight recommended in deep/high current deployments. | Single body on main umbilical (live boating) or Tether Management System (TMS). | Single body on main umbilical (live boating) or TMS. |

| Approx. survey cost per day* | AUD 2,000 - 10,000 | AUD 5,000 - 40,000 | AUD 50,000 - 120,000 |

| Approx. purchase cost^^ | AUD 10,000- 250,000 |

AUD 200,000- 1,000,000 |

AUD 1,000,000- 6,000,000+ |

| Vessel requirements | Fixed platform (jetty/pontoon/oil/gas platform), small vessel (<10m) (with or without power supply) or other small vessel. | Shallow draught vessels suitable for inshore waters (10-30m), for extended offshore surveys larger (~>30m) vessels will be used. | Large vessel (~>50m) with Dynamic Positioning (DP), deck capacity for container storage and LARS. |